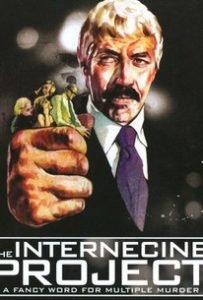

(1974, PG) James Coburn (Prof. Robert Elliot), Lee Grant (Jean Robertson), Harry Andrews (Bert Parsons), Ian Hendry (Alex Hellman), Michael Jayston (David Baker), Christiane Kruger (Christina Larsson), Keenan Wynn (E. J. Farnsworth), Julian Glover (Arnold Pryce-Jones). Music: Roy Budd. Screenplay: Barry Levinson and Jonathan Lynn (based on “Internecine” by Mort W. Elkind). Director: Ken Hughes. 99 minutes.

(1974, PG) James Coburn (Prof. Robert Elliot), Lee Grant (Jean Robertson), Harry Andrews (Bert Parsons), Ian Hendry (Alex Hellman), Michael Jayston (David Baker), Christiane Kruger (Christina Larsson), Keenan Wynn (E. J. Farnsworth), Julian Glover (Arnold Pryce-Jones). Music: Roy Budd. Screenplay: Barry Levinson and Jonathan Lynn (based on “Internecine” by Mort W. Elkind). Director: Ken Hughes. 99 minutes.

Tags: Suspense, Thriller, Spy vs. Spy

Notable: New meaning to the phrase “Timing is everything”; reliance on low-tech gimmicks, for the most part

Rating: ★★★★☆

Robert Elliot (Coburn) is a renowned professor of economics who is about to be promoted to the highest chairmanship in the U.S. government policy-making committee. He is also a former corporate spy who must get rid of anyone or anything associated with his dark past. As the masters of intrigue would say, he must “clean up his network,” which means killing four people. He creates a perfect plan that some call the Circle of Death – in a single night, his former associates will kill each other, in a perfect circle of mutually assured destruction.

The word “internecine” (in-ter-NEE-sine) is an adjective meaning “destructive to both sides in a conflict.” The tag line of the original movie trailer ruins the effect by calling it “a fancy word for multiple murder.” It’s irritating that the movie company mislabels the word so terribly, because the word itself, in its original and true sense, is brilliantly accurate. Frankly, however, most people (myself included) wouldn’t have known what it meant until it was explained to them. The word defines both the mutual destruction of each murderer/victim as well as the effect of the entire complicated intrigue upon its creator. The plot is a Mission: Impossible-like treasure of the coordination of time-tables, signals made by the number of rings on a telephone, and ingenious means of bringing death to each of the four spies, none of whom knows the others. It’s a perfect plan… if it works.

There is something in this film that makes me wonder if the Columbo franchise owes it some small debt of gratitude. The script is co-authored by Barry Levinson who, with William Link, created the trench-coated detective. (The other co-author, Jonathan Lynn, penned the wicked script for Clue, among other films.) We see the motivation of the killer (or perhaps, in this case, the organizer of the killings — Coburn), we see the careful plotting of the killings, and we see what happens as each attempt is made. A machine is only a perfect as its weakest cog (to coin a phrase), and there’s no guarantee that any plan can be performed flawlessly. Suspense begins from the opening sequence, as we try to understand why someone would be walking to various locations in London, measuring distances with a stopwatch.

At its heart, this film is not particularly complicated; what makes it work is a combination of the tension created by wondering if the outlandish clockwork of assassinations will work and the mixture of character types demonstrated superbly by the principle actors. Coburn has often played bad guys, or at least people of questionable ethical verity. Just two years prior to this, he portrayed the film producer in the murder mystery The Last of Sheila; he is described by another character as “a minor-league sadist”. In The Carey Treatment of that same year, he portrays a doctor who may or may not be a good guy as he investigates a mysterious death at the hospital to which he had just transferred. (That film, by the way, was based upon the novel A Case of Need, by Jeffrey Hudson — pen-name of a then-in-medical-school doctor named Michael Crichton.)

Of the various character actors portraying the killer/victims of this circle of death, the most well-known to me is Harry Andrews (The Medusa Touch, Equus). A solid performer in every role I’ve seen him deliver, he provides an interesting mix of intensity and subtlety to this character — ex-military, a little too tightly wrapped, and covertly homosexual at a time when, in England, it was a crime simply to be homosexual. Coburn uses his blackmail and influence delicately, and Andrews delivers a performance with a combined sense of eagerness to please and irritation at the blackmail. He’s rather like a faithful old bulldog who strains at his collar partly because he’s eager for action and partly because he resents the chain.

Keenan Wynn (The Great Race, Pretty Maids All In a Row) made an entire lifetime out of small roles, never once seeming to resent it. The son of Vaudevillian actor Ed Wynn, he inherited the best of his father’s genes. In his supporting characters, he always brought something special to each one — a quirk, a delivery of line, a mannerism. Never over-the-top (unless the role called for it), he nevertheless was one of those actors who, once you’ve seen his name in the opening credits, you watch for with great glee.

A satisfying watch, although little-lauded these days. Leonard Maltin dismisses it as “lackluster,” giving it two stars out of four. Clearly, we disagree.