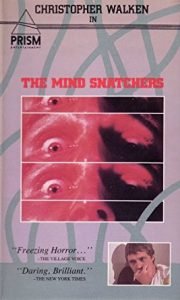

(1972, not rated) Christopher Walken (Pvt. James Reese), Joss Ackland (Dr. Frederick), Ralph Meeker (The Major), Ronny Cox (Sgt. Boford Miles), Marco St. John (Shannon). Music: Phil Ramone and Chris Dedrick (performed by Free Design). Screenplay: Ron Whyte, based on the play The Happiness Cage by Dennis Reardon. Director: Bernard Girard. 94 minutes.

Notable: Christopher Walken’s first starring role.

Rating: ★★★☆☆

Army Private James Reese has anger issues, which lands him in a highly secluded and heavily secured country estate somewhere in the West German countryside. He and two other American soldiers are under the exclusive care of Dr. Frederick, who seems to be anything but an ordinary general practitioner. As Reese discovers that his orderly, Shannon, behaves more like a sadistic prison guard, and that his doctor has a separate laboratory with monkeys who appear to have had some sort of surgery performed upon their brains, he comes to realize that his presence is less for recovery than it is for experimentation.

Considered daring and cutting-edge for its time (the ending credits include a full-page reproduction of a Newsweek magazine cover showing a monkey with electrodes implanted into its skull), the film might be thought blasé by modern standards. What keeps it worth watching in this brave new world of in-your-face mind-control movies is the dual-edged sword of subtlety of presentation and discussion of the morality of the actions involved. It’s a “talking heads” sort of film, meaning that there’s really very little physical action and virtually no special effects of any kind. What the heads are talking about, however, is something that bears listening to. In a sense, the first 80 or so minutes of the film exist exclusively for the watcher to experience in full the exquisitely grotesque sense of revulsion at the ending.

Christopher Walken is famous for observing that, “If you want a Chris Walken sort of character in your movie, you have to get Chris Walken to play him.” This film demonstrates, in his first starring role, precisely what he’s talking about. For a character who is supposed to be violent, Reese actually demonstrates very little physical violence; his attitude, however, is utterly sociopathic. Walken rarely blinks, makes not the merest unneeded movement, wastes no unnecessary vocal inflection. Even with this character who seems not to have a single likeable or relatable trait, not a single thing with which the viewer could claim empathy, there is still a certain sense of utter horror in what ultimately happens to him.

You might know Ronny Cox from such roles as corporate bad guy “Dick” Jones in the original Robocop (1987), or perhaps even from Total Recall (1990) as the equally egregious Mars administrator Vilos Cohaagen. (If you’re a gamer: He provides a voice in 2004’s Killzone.) In 1972’s Deliverance, he actually played the guitar part of the famous musical challenge “Dueling Banjos,” and was in fact hired for the role largely because of that skill. He’s no slouch as an actor, however. His purpose here (only his second role in a feature film) is to provide a much more obvious example of a “nut case” to juxtapose against Walken’s quietly creepy sociopath. It’s an interesting question, for many viewers, which one of the two gets a more just result out of the deal. It’s worth splitting a pizza and some root beers to debate over. Saying more might be considered too much of a spoiler.

A word needs to be mentioned regarding the minimal amount of music that is used as the soundtrack for this movie. That word is “inappropriate.” It’s not bad; it just doesn’t fit the scenes that it is meant to underscore. It would have been interesting to hear what some of the pioneers of electronic film scores of that time period (e.g., Gil Mellé, who scored The Andromeda Strain (1971) and A Cold Night’s Death (1973)) could have done to intensify the effect of the work. In my opinion, properly used, such a score could have added another full star to the ranking.