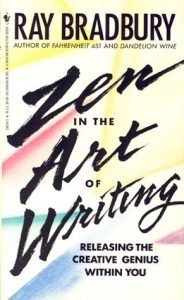

By Ray Bradbury

By Ray Bradbury

ISBN 0-553-29634-5

Publication Year: 1990

Tags: Writing, Art, Life, Philosophical

Rating: ★★★★★

“Every morning, I jump out of bed and step on a landmine. The landmine is me. After the explosion, I spend the rest of the day putting the pieces together. Now, it’s your turn. JUMP!”

(Bias warning: Ray Bradbury was my mentor, so I’m already predisposed to enjoy his work.)

It would be an incredible disservice to call this book a “writer’s manual” or a “how-to-write guide.” For any one writer to tell you how to write is ridiculous. “Papa” Hemmingway would teach you never to use a semicolon. Raymond Chandler, creator of Philip Marlowe, once advised (perhaps in jest), “When in doubt, have a man come in through the door with a gun in his hand.” Richard Brautigan and Paul Auster, like Jack Kerouac before them, would tell you to abandon sense and reason in favor of winding up your reader and letting him founder in an ocean of irrelevancies, and too bad if they don’t “get it.” Elmore Leonard’s “Ten Rules of Writing” include not developing or detailing characters and locations, carrying dialog only with the word “said,” and “leaving out the part that readers tend to skip.” Every writer has his followers (I love Chandler), but no writer can tell you what or how to write. This includes Bradbury.

What he offers in this book is as much about life as it is about being a writer, an artist, an explorer, a living being in an amazing world. He speaks passionately about passion, about zest, about gusto, about not “keeping an eye on the commercial market” but instead looking within and without to find your truest voice, the stories that only you can write. In the brief preface to the book, he exhorts us to remember “that we are alive, and that it is a gift and a privilege, not a right… Writing is survival. Any art, any good work, of course, is that. Not to write, for many of us, is to die.” Add to this my favorite quote: “You must stay drunk on writing so that reality cannot destroy you.”

He offers practical advice as well, but he does so in the context of suggesting how you can begin to find that creative genius within. Bradbury describes a list of words, like items in a treasure hunt, “simply flung forth on paper, trusting my subconscious to give bread, as it were, to the birds.” He speaks of the act of writing a thousand words a day, perhaps a story per week, and that in a year, you will have at least 52 stories. Many will be awful, some will show some promise, and a few will be genuinely good. This he compares to the way that a surgeon must cut up a thousand cadavers before his hand can guide the scalpel to work upon living flesh, or how an artist might copy the work of the masters before he trusts himself to let his own art begin to flow. (Oh, how many of the stories I wrote in my high school years were good? None! I’m grateful that none survive now. I am also grateful for what each one showed me, before I made my first national publication in November 1977, and more and better to this day.)

Let me offer a long quote, about the lists…

I began to run through those lists, pick a noun, and then sit down to write a long prose-poem-essay on it. Somewhere along about the middle of the page, or perhaps on the second page, the prose poem would turn into a story. Which is to say that a character suddenly appeared and said, “That’s me”; or, “That’s an idea I like!” And the character would then finish the tale for me. It began to be obvious that I was learning from my list of nouns, and that I was further learning that my characters would do my work for me, if I gave them their heads, which is to say, their fantasies, their frights.

Over the years, I have taken this advice to heart. To this day, I speak of how characters come to me to tell the stories that they could not. My award-winner “White Nights” is about this very idea. (Thank you, my literary Master, for helping this supplicant see… and more importantly, listen!)

There is also the more philosophical advice, which he sums up with four words: WORK. RELAXATION. DON’T THINK. I could try to explain, but Bradbury’s eloquence is far better than my own. I’ll let him tell you all about it, along with how he had never wanted to go to Ireland, yet there (along with penning the screenplay to John Huston’s 1956 film of Moby Dick) he discovered — years later — the memories of people, of places, of things that inspired so many of his greatest stories (“McGillahee’s Brat,” “The Anthem Sprinters,” “A Great Conflagration Up at the Place”), one- and three-act plays, and the novel Green Hills, White Whale. Let him explain to you “How to Keep and Feed a Muse,” or what it means to be “Drunk, and In Charge of a Bicycle.” Let his poems, at the back of the book, explain to you how to “Go Panther-Pawed Where All the Mined Truths Sleep,” and to explain why “I Die, So Dies the World.”

You might find a book to tell you, step by step, how to write. Good luck with that. What you’ll gain from this book is a sense of passion, wonder, great joy, and great purpose. To write with Your Voice — and only you can write with that voice — read and feel the sense of opening yourself wide to the possibility of being truly alive. That’s what this book is for. That’s what the essence of creativity is all about. Set your feet upon this road and see what a marvel you, the budding writer, really are.

Fair to say that I really like this book. Now it’s your turn. Jump!