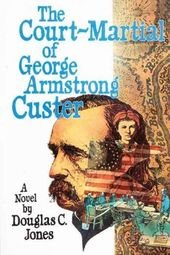

By Douglas C. Jones

By Douglas C. Jones

ISBN: 0-684-14738-6

Publication Year: 1976

Tags: Historical Fiction, What-If, Native American, Military History

Rating: ★★★☆☆

George A. Custer, ranked as a General in the War Between the States but who was returned to the rank of Lt. Col. during his time commanding the 7th United States Cavalry, died at Little Big Horn. This what-if historical novel considers the question of Custer’s survival, and what a court-martial might find of the evidence presented to it of Custer’s actions that lead to a head-to-head battle of several hundred cavalrymen against several thousand Native Americans — or as they’re called in this book, with both historical accuracy and a conqueror’s prejudice, “Indians,” “renegades,” or “criminals who wouldn’t stay on the reservation”).

I found this to be an interesting, courtroom-drama-style read, with great attention to historical detail and a great deal of rather horrible information about the infamous battle at Little Big Horn; it’s a good read for both of those reasons, as well as a properly damning look at the idea of the highly dangerous procedure known as the military tribunal. I should warn one and all that this review contains what may be called “spoilers,” although they really shouldn’t spoil reading the book even if you know about them.

POSSIBLE SPOILER: Any military tribunal must weigh the value of prosecuting the crime being leveled against the officer in question versus the dangerous effects of setting command-stifling precedent. If a military commander must second-guess whether or not his actions might come under scrutiny of legal action, it could seriously compromise his effectiveness in the field. Consequently, it is almost certain from the first page of this book just exactly where the tribunal will fall in its judgment of Custer. (For an excellent depiction of this concept in film, enjoy Breaker Morant.)

FULL SPOILER: They acquit the white man, of course — although to Jones’ credit, they do so by thin margin and with great disgust. It’s a good thing that Custer really did die at Little Big Horn, because he was (by historical accounts quoted in Jones’ book) a preening, politically-ambitious popinjay who is responsible not only for the deaths of hundreds under his command but also for the severe escalation of the Indian wars. As a Cheyenne myself (we and the Sioux were principles in this battle), I’m disgusted with the defense of Custer’s actions, even bearing in mind the [particularly obscene expletive self-deleted]’s “duty” as a military man. What makes the book of greater interest, however, is that it paints Custer’s wife Libby as the driving force behind the political aspirations of a little boy seeking his mother’s approval. This rather Freudian view is in keeping with the historical record, seen through a psychological profiler’s lens; it brings Custer’s actions into sharper relief, in one sense, by showing that it was not his military duty so much as his other-motivated political ambition that caused him to try to become “The Man Who Destroyed the Indian Menace.”

My less-than-full-rave-review is due to the somewhat plodding nature of the book – something that, sadly, can be said of many examples of courtroom genre fiction. Testimony must be heard, and in a military tribunal or court-martial, the rules are particularly strict. Despite this drawback, I vouchsafe that I would recommend this book to those who like courtroom dramas, historical “what-if” fiction, and/or Native American studies, as it does provide an intricately detailed look at the actions of those who fought at the Little Big Horn, on both sides. It also shows how the government and the military viewed Native Americans during that time, and (forgive my two cents) not that much has changed, sadly. The United States has a bloody history of aggression and violence against non-white people, both within and without its borders; this trend began before the nation was founded, and it has continued with little improvement into the 21st century. I wish not to express any partisan view here; the point is evident through the lens of history.