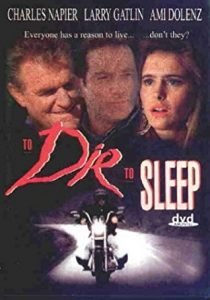

(1994, Rated PG-13) Noah Hathaway (Phil), Paul Coufos (Dumar), Larry Gatlin (himself), Ami Dolenz (Kathy), Charles Napier (Father), Trish Davis (Mother), Nicole Fellous (Jan), Suzanne Alter (Sue), Vali Ashton (Counselor), Tom Pieper (Drug Dealer), George Thompson (Bartender). Music: Ralph Geddes and Michael G. Smith. Screenplay: Rick Filon (story by Kenneth Dalton and Rick Filon). Director: Brianne Murphy. 86 minutes.

(1994, Rated PG-13) Noah Hathaway (Phil), Paul Coufos (Dumar), Larry Gatlin (himself), Ami Dolenz (Kathy), Charles Napier (Father), Trish Davis (Mother), Nicole Fellous (Jan), Suzanne Alter (Sue), Vali Ashton (Counselor), Tom Pieper (Drug Dealer), George Thompson (Bartender). Music: Ralph Geddes and Michael G. Smith. Screenplay: Rick Filon (story by Kenneth Dalton and Rick Filon). Director: Brianne Murphy. 86 minutes.

Tags: Teen, Angst, Suicide, Avoid-At-All-Cost

Notable: The characters are so two-dimensional, most don’t even have names (Father, Mother, etc.), and the script is the same.

Rating: ☆☆☆☆☆

A troubled teen — a rich kid who would rather have his parents than their money — begins to flirt with death as a way to ease his pain. He meets a roadie with a C&W band who offers his experience to help him choose a different course.

(Quick side note: Did you notice the picture of the DVD cover? The two leads, Hathaway and Coufos, aren’t even listed. The three stars listed have, perhaps 12-14 minutes of screen time, total. I can find no reason nor explanation, but it bodes ill, I would say.)

The film begins reasonably well; the acting and script are sufficient that one doesn’t fall asleep right away. There are, in fact, a few good lines, including some that actually reach into the heart of what it’s like for a teen to consider suicide. (The following is not really a spoiler, as it’s telegraphed from early in the film.) When Kathy (Ami Dolenz, daughter of Monkees rocker Mickey Dolenz) shoots herself in the restroom of a local nightclub, it’s a reasonably believable action for her character to take.

What infuriates me about this film is its utter cowardice in facing the issue of teenage suicide directly. The script creates a truncated formula for teen suicide: My parents hate me, nothing I do has any meaning, no one cares about me, and I didn’t ask to be born, so I’ll just let myself back out of this life. While these ideas may be part of what leads a teen to kill himself, they are not part and parcel. Suicide is a terrifyingly individual choice, and the reasons to attempt (or even succeed in) killing oneself are not easily found or understood. One of the more famous stories of teen suicide concerned a particularly popular girl who had good grades and many friends; after being crowned Homecoming Queen, she went home and shot herself. The note that she left behind explained that she had accomplished everything that she could, and that there was nothing left to strive for.

Noah Hathaway, most memorable as Atrayu in The Neverending Story, has transformed from handsome youth to surly, semi-punked teen without a hitch. His character has little to recommend him. His “suicide formula” is essentially that of The Poor Little Rich Kid. The parents, who are so two-dimensional that they are only called “Father” and “Mother” in the credits (as are all of the adults, save for the “hero”), are of no particular help either. Said hero, Dumar (Coufos), is clearly to be Phil’s savior, and for reasons that are obvious from the first time he tugs at his conspicuously ever-present neckerchief. The Big Revelation: Rope burns, from when he tried to hang himself some years ago. His advice: “If [the boy] thinks someone cares about him, then maybe he’ll care about himself a little.” At first glance, this advice appears to fly in the face of the “love yourself first” philosophy, but when you hate yourself enough to want to murder yourself, then you might want to hope that someone else might want to help pull you back from the brink.

Sadly, this platitude was stuck in as “too little, too late” in the film. Worse, it is overshadowed by the excruciatingly stupid ending. As Dumar takes his leave, he says to Phil, “If you ever need to talk to somebody, here’s the business card of someone I can recommend.” With this, he hands to the boy — are you sitting down? — a gold cross on a neck chain. To make this travesty worse, Phil rides his motorcycle to a local country church and finds a man standing near the altar, singing a song about “I’m Still Here” (no, not the Sondheim song). Song over, the man asks the boy, “Can I help you find someone?” Phil replies, “No — I think I found him.”

I’ve been told that my attitude toward religion is both glib and condescending. This is because religion is both glib and condescending toward people in real pain and serious trouble. Individuals, whether of holy orders or the laity, can be extremely helpful and might even save lives; religion itself, as an entity and an unforgiving travesty of faith, has caused more deaths (including suicide, murder, and genocide) than any other non-natural cause in the history of humankind.

I resist having a rating of zero stars; I feel that any genuinely creative production deserves some credit. This was the first film that I have given a zero rating to; I can think of only one other, and I’ll talk about that one elsewhere. I rate this film zero for insulting our intelligence, for glossing over a deeply painful and serious subject, for superficiality that borders upon the criminal, and for abusing the medium of film by promoting an unconscionable triviality as a cure for a rapidly-increasing epidemic worldwide. Having lost friends both to the tyranny of religion and to the horror of suicide, I find this film offensive to the point of demanding that those involved in it and/or responsible for it make appropriate amends.